With these cold, wet, winter days still upon us we at Moggyblog have turned our attention to a cat that has very little hair or fur and some are even classed as ‘nude.’ How they ever coped with sub-zero Russian winters we can only guess.

The beautiful Peterbald breed was first developed in 1993-4, when (it is said) a Russian breeder named Olga S. Mironova crossed Afinguen Myth, a brown tabby Donskoy, with an Oriental Shorthair female by the name of Radma Vom Jagerhof. At the time their offspring were gaining popularity in St. Petersburg, Russia, and they were quickly pronounced with the new title Peterbald. New breeding lines were created as Peterbalds were consistently bred out to Donskoy, Oriental Shorthairs and Siamese. TICA accepted the Peterbald in 1997 and recognized them for championship status in 2005.

Although recognised by The International Cat Association (TICA) since 1997, the Peterbald is still a relatively rare purebred or pedigreed domestic cat breed.

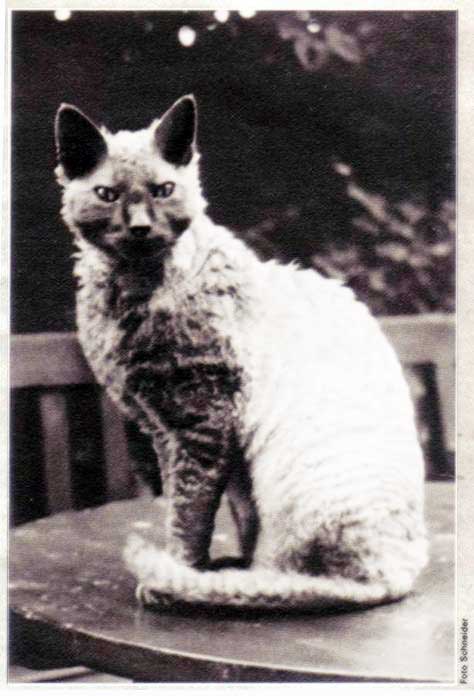

Like the the Don Sphyx, the amount of hair or fur on a Peterbald can vary greatly from cat to cat. There’s even an “Ultrabald” type that doesn’t even have whiskers or eyebrows and they and never grow any hair at all. Then there is Flock or Chamois variety being ninety percent hairless. These cats have a soft silky feel. Other varieties of coat include Velour, Brush coat and Straight coated. However these coats can change significantly throughout their first two years of life, and their hair texture alter as time goes by either by gaining or loosing hair.

The Peterbald took its long and fine-boned, lithe body type and oblong head shape from the Oriental Shorthair. One unique feature about Peterbalds is that they have long front toes with webbing, which allows them to hold and manipulate toys and other items. Their tails are strong and thin with a graceful curl.

The breed are known to be intelligent, very active, friendly and playful, but because they are highly sociable they should always have companions around them, be these human or feline in origin. They can be fine lap cats in spite of their active natures. When venturing outdoors, care must be taken with the hairless Peterbald, as they are sensitive to very hot and cold weather. Sunburn and other skin issues are also potential concerns.

For keepers of Peterbald cats regular bathing is an important part of the weekly grooming routine. This will prevent the build up of oils on the cats skin, and will also remove daily dirt which may cause irritation. A vets advice should be sought which products to use.

Finally if you are drawn to purchase a beautiful Peterbald cat from a breeder, always investigate any hereditary or genetic conditions by asking about the breeding process. Kittens can also be examined by a vet to provide you with peace of mind before a purchase.

So, like all cat lovers, there is every excuse to stay home and dry and snuggled up with your Peterbald (or any other type of cat, for that matter) this winter and, for the Peterbalds, for the rest of the year too…